Rotating wave approximation

The rotating wave approximation is an approximation used in atom optics and magnetic resonance. In this approximation, terms in a Hamiltonian which oscillate rapidly are neglected. This is a valid approximation when the applied electromagnetic radiation is near resonance with an atomic resonance, and the intensity is low. Explicitly, terms in the Hamiltonians which oscillate with frequencies  are neglected, while terms which oscillate with frequencies

are neglected, while terms which oscillate with frequencies  are kept, where

are kept, where  is the light frequency and

is the light frequency and  is a transition frequency.

is a transition frequency.

The name of the approximation stems from the form of the Hamiltonian in the interaction picture, as shown below. By switching to this picture the evolution of an atom due to the corresponding atomic Hamiltonian is absorbed into the system ket, leaving only the evolution due to the interaction of the atom with the light field to consider. It is in this picture that the rapidly-oscillating terms mentioned previously can be neglected. Since in some sense the interaction picture can be thought of as rotating with the system ket only that part of the electromagnetic wave that approximately co-rotates is kept; the counter-rotating component is discarded.

Mathematical formulation

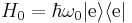

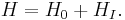

For simplicity consider a two-level atomic system with excited and ground states  and

and  respectively (using the Dirac bracket notation). Let the energy difference between the states be

respectively (using the Dirac bracket notation). Let the energy difference between the states be  so that

so that  is the transition frequency of the system. Then the unperturbed Hamiltonian of the atom can be written as

is the transition frequency of the system. Then the unperturbed Hamiltonian of the atom can be written as

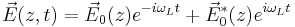

Suppose the atom is placed at  in an external (classical) electric field of frequency

in an external (classical) electric field of frequency  , given by

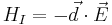

, given by  (so that the field contains both positive- and negative-frequency modes in general). Then under the dipole approximation the interaction Hamiltonian can be expressed as

(so that the field contains both positive- and negative-frequency modes in general). Then under the dipole approximation the interaction Hamiltonian can be expressed as

where  is the dipole moment operator of the atom. The total Hamiltonian for the atom-light system is therefore

is the dipole moment operator of the atom. The total Hamiltonian for the atom-light system is therefore  The atom does not have a dipole moment when it is in an energy eigenstate, so

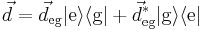

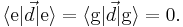

The atom does not have a dipole moment when it is in an energy eigenstate, so  This means that defining

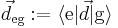

This means that defining  allows the dipole operator to be written as

allows the dipole operator to be written as

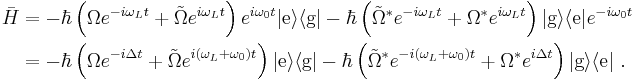

(with ` ' denoting the Hermitian conjugate). The interaction Hamiltonian can then be shown to be (see the Derivations section below)

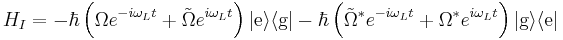

' denoting the Hermitian conjugate). The interaction Hamiltonian can then be shown to be (see the Derivations section below)

where  is the Rabi frequency and

is the Rabi frequency and  is the counter-rotating frequency. To see why the

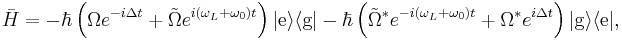

is the counter-rotating frequency. To see why the  terms are called `counter-rotating' consider a unitary transformation to the interaction or Dirac picture where the transformed Hamiltonian

terms are called `counter-rotating' consider a unitary transformation to the interaction or Dirac picture where the transformed Hamiltonian  is given by

is given by

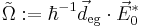

where  is the detuning of the light field.

is the detuning of the light field.

Making the approximation

This is the point at which the rotating wave approximation is made. The dipole approximation has been assumed, and for this to remain valid the electric field must be near resonance with the atomic transition. This means that  and the complex exponentials multiplying

and the complex exponentials multiplying  and

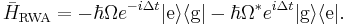

and  can be considered to be rapidly oscillating. Hence on any appreciable time scale the oscillations will quickly average to 0. The rotating wave approximation is thus the claim that these terms are negligible and the Hamiltonian can be written in the interaction picture as

can be considered to be rapidly oscillating. Hence on any appreciable time scale the oscillations will quickly average to 0. The rotating wave approximation is thus the claim that these terms are negligible and the Hamiltonian can be written in the interaction picture as

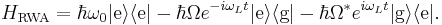

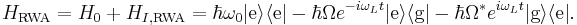

Finally, in the Schrödinger picture the Hamiltonian is given by

At this point the rotating wave approximation is complete. A common first step beyond this is to remove the remaining time dependence in the Hamiltonian via another unitary transformation.

Derivations

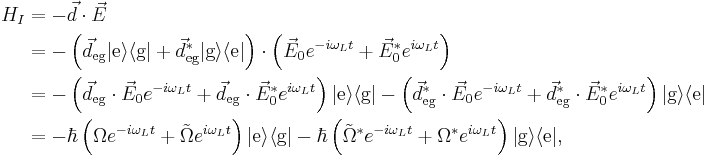

Given the above definitions the interaction Hamiltonian is

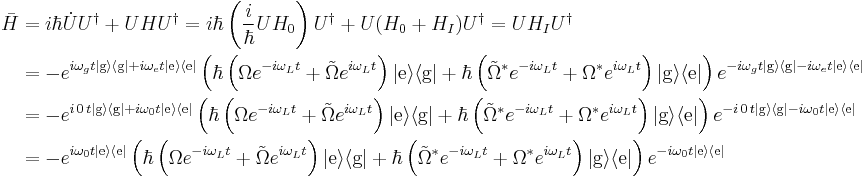

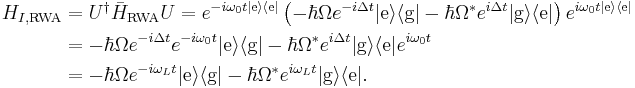

as stated. The next stage is to find the Hamiltonian in the interaction picture,  The unitary operator required for the transformation is

The unitary operator required for the transformation is  and an arbitrary state

and an arbitrary state  transforms to

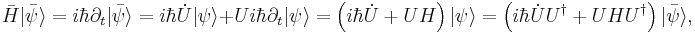

transforms to  The Schrödinger equation must still hold in this new picture, so

The Schrödinger equation must still hold in this new picture, so

where a dot denotes the time derivative. This shows that the new Hamiltonian is given by

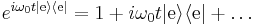

Using a Taylor series expansion of the exponential,

and operating on

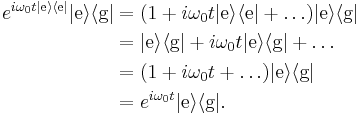

Operating from the left on the second term of  above yields zero by orthogonality of

above yields zero by orthogonality of  and

and  , and the same results apply to the operation of the second exponential from the right. Thus, the new Hamiltonian becomes

, and the same results apply to the operation of the second exponential from the right. Thus, the new Hamiltonian becomes

The penultimate equality can be easily seen from the series expansion of the exponential map and the fact that  for i and j each equal to e or g (and

for i and j each equal to e or g (and  the Kronecker delta).

the Kronecker delta).

The final step is to transform the approximate Hamiltonian back to the Schrödinger picture. The first line of the previous calculation shows that  , so in the same manner as the last calculation,

, so in the same manner as the last calculation,

The atomic Hamiltonian was unaffected by the approximation, so the total Hamiltonian in the Schrödinger picture under the rotating wave approximation is